So some people asked me to share my symposium presentation about building myth in creative writing. Your wish is my command! Here’s my abstract:

The world is not constructed simply of fact, but also of myth. The interplay between mythology, geography, culture and history is a relationship which fiction provides a perfect platform for exploring. This presentation will focus specifically on Welsh and Celtic mythology, a relatively unknown genre of myth, before exploring the ways studying the influences of myth can help create worlds in fiction. Welsh mythology is closely tied to its geographic roots, with many tales informing the listener specifically where the events are said to have taken place. This connection between land, history and legend will be examined in the stories Culhwch and Olwen from the Mabinogion and The Prophecy of Merlin from the History of the Kings of Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth, both of which have powerful connections with Welsh culture even today. Finally, an excerpt from my own work in progress, Blessings, will be read to demonstrate how I have utilized my research to create a world with its own myths, history, and place. Drafts and notes will be read to show how I created my world based on what I have learned about myths and fairytales in Wales.

The Role of Mythology in Fiction

Characters are formed not just by their own personal history, but the landscape, history and myth surrounding the world they live in and react to. A Texan is not a New Yorker and a Welshman is not an Englishman, in a large part because of the myths that grow from their surroundings and flavor their culture. In Myths and Legends of Wales, a collection formed solely around the locations of legends, author Tony Roberts writes, “There is a special fascination for most of us to realize, in a particular village or field or house, that something strange took place a hundred or a thousand years before. […] Folk-tales [are] not just fairy tales for adults, but [are] vital and important as part of the history and culture of a nation.” Considering that the landscape and myths that surround people are so vital to their development as individuals, it is impossible to create developed fictional characters—even ones in a fantastical world—without giving some thought to the myths and landscape of their world. With this in mind, I will briefly examine the ways Welsh mythology was influenced by landscape and in turn influenced Welsh culture. Then I will read excerpts of my own fiction to show ways that I have used my research on this relationship between landscape, history and myth to create my own characters in my own fictional world.

Welsh mythology offers a unique legend tradition in which to explore the relationship between theses forces that form and challenge a character. We will be looking at two well-known Arthurian legends, both steeped in landscape and Welsh identity. But first, a quick observation about Welsh history. The Bretons—the Welsh’s ancestors—were the original inhabitants of the Isle of Britain. They were pushed back by the Anglo-Saxons into the area that is now Wales. What we call the “British” were then considered the Anglo-Saxons. To this day, the Welsh maintain a spirit of rebellion—which can be seen frequently in their legends.

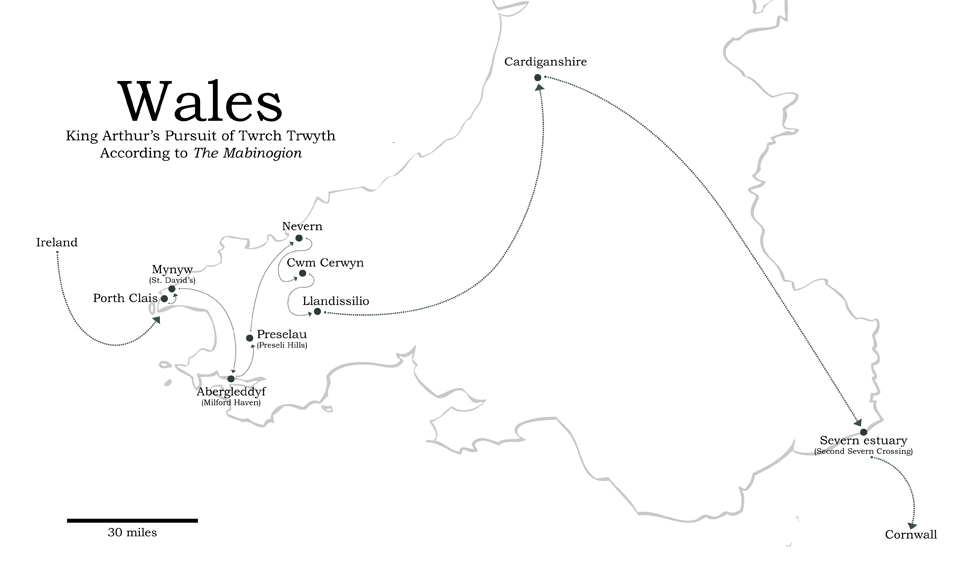

The Mabinogion contains several famous Arthurian stories, one of which is Culhwch and Olwen. This is the oldest surviving narrative tale of King Arthur and is inseparably connected with the landscape of Wales. In Culhwch and Olwen, Culhwch asks his cousin, King Arthur, to help him win the hand of the daughter of a giant. In order to do this, King Arthur and warriors from across the Island of Britain and beyond are given thirty-nine impossible tasks to complete. One task involves getting a comb, razor and scissors from the boar Twrch Trwyth. Though they go to visit the boar in Ireland, Twrch Trwyth takes the battle to Arthur’s home ground and is chased across modern-day Wales, from Mynyw (modern day St. David’s) to Cornwall. The location descriptions in this story are so specific that they can be mapped today—which you can see below.

The detail is remarkable for our discourse. Here, Arthur is truly his original self—fully Breton, without undergoing the character changes that will happen under the hands of the German, French or English. He is represented as protector of the Isle of Britain against outsiders in his pursuit of Twrch Trwyth, who eventually must flee the country. In order for people to fully understand an Arthur who is fully Breton, they must understand the Preseli Hills’ rolling green sprinkled with bone breaking boulders, Nevern’s mist-cloaked cliffs and rushing tides, Cardiganshire’s high hills and deep valleys, and the wide Severn River separating Wales from England. Without seeing the diversity of the land through which Arthur and his men travel, a reader would not understand the wild diversity of the Welsh themselves.

One particularly vital legend in Welsh mythology is the story of The Prophecy of Merlin. In Welsh tradition, Vortigern, King of Britain, goes to Eryri (present-day Snowdon) to build a castle. But what is built during the day is found destroyed after every night. Vortigern is told to find a fatherless boy to sacrifice, and Merlin is brought to the scene. Though a mere boy, Merlin takes charge and reveals to the king that there are two dragons under the foundation: One white, one red. The white dragon represents the Saxons and the red the Bretons. The cavern is a symbol of the world. Because the red dragon eventually defeats the white, Merlin prophesies that at first the invader will triumph, but the Welsh will one day be free again.

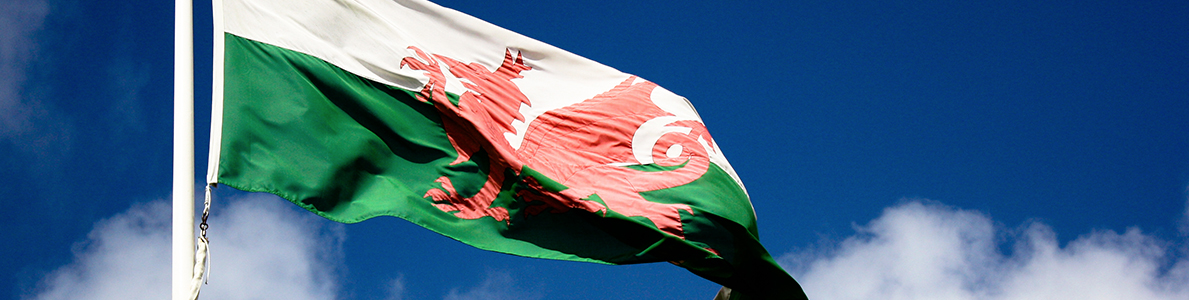

This red dragon is the present-day symbol of Wales and is displayed on the Welsh flag. The extent to which this story was taken to heart can be seen in the eleventh century of Welsh history. Wales was divided into two primary kingdoms, and two men believed themselves to be the rightful heirs to the kingdoms in the north and south. One man, Gruffudd ap Cynan, claimed that he was the mighty king of Welsh and Viking blood as foretold by Merlin. That was how strongly legend informed identity—to the point where people drew their bloodline down from imaginary figures and read legendary prophecies into their future.

If this identification with legend and land is so powerful in societies past and present, why not employ it in fiction to create well-rounded worlds and characters? This question was on my mind as I traveled in the United Kingdom while working on my novel-in-progress, Blessings. I began to create my own mythology for my story and to build a world that responded to its history of legend. I will now read three excerpts showing different ways I worked the mythology into my fiction. Please refer to below for character names.

Eleazar – King of the fair realm

Melle – Unblessed peasant helping Velimir

Velimir – Prince in human kingdom (Bhàtar)

In the following scene, one of the fair folk speaks to a human, Velimir. This is an oral tradition told from the perspective of a witness, and represents the very beginnings of the tradition of legend in my tale.

Eleazar and I had heard legends of a great tree, the source of all the magic in the world. Having little hope, we searched, believing it might hold the secret that would save our people. One night, Eleazar went ahead without me. I followed and saw him as he knelt before a being, a spirit, who leaned out toward him from the trunk of a mighty oak. The spirit’s face was weathered and aged gray-brown, like a dying tree. Its hair was a mass of tangled branches, its arms long and gnarled.

The spirit uncurled one long, pointed finger, and touched Eleazar’s forehead. My beloved cried in pain. I ran to him, but the spirit’s sharp amber eyes stopped me with a warning. Deep brown like the bark of a tree spread from the spot on Eleazar’s forehead down his body. I stood by as he transformed before my eyes. He became what he is.

He had made a trade with the spirit. Of the spirit, he had asked for a forest suitable for his people, one which would be a danger to men who dared trespass. In exchange, the spirit wanted simply to die, to find peace by giving its magic, its knowledge, its very essence to another living being. The fair realm was created—a safe haven for our kind, a danger to mortals. The magic of the forest, flowing from the tree and from Eleazar, stops time itself within the wood.

In the following scene, the characters see the tree mentioned above. This is an example of the way legend can form the creation of a world. Eleazar’s fair realm is divided into four different seasons, which in turn influences the description of the tree. This is also an example of legends can change the way a character perceives his or her surroundings. Melle, the narrator in this scene, is aware enough of the myths of her world to interpret her surroundings without being all-knowing.

In patches the soil had eroded, leaving twisted roots knotted over each other. The patterns dented Melle’s feet through her soft soled shoes. Gaps revealed more roots beneath, layers upon layers of roots. Melle picked her way carefully, wary of holes wide and waiting for an ankle to break. A heaviness settled around her, a reverence in the very air she only understood when she crested the little rise.The raised circle of roots expanded on either side before Melle. Directly opposite her, separated by the span of two fields, an oak tree dwarfed everything—the great forest around mere twigs, the fair folk grains of dirt. The lowest branches spread above at least four times a normal man’s height. Leaves of bright and dark green, red and yellow and white created a paradox, as if it contained all seasons at once.

The center of all magic, Velimir had told her. The Antharen.

The fair court itself would have been in relative darkness, cast by the trees’ shadows, but for orbs, glowing like small moons, suspended by gossamer string above the fair folk. Fireflies flickered between the orbs. The floor was a carpet of leaves—all the brilliant colors of autumn, not the brittle browns of a dying season.

In my final excerpt, you can see the pieces of the first two merging together—the legend, the characters formed from their legends, and the way these legends and characters impact others. The fair one’s home and heritage comes down even to her use of magic—the magic is in her very blood, inseparable from her. The following excerpt shows a displaced fair one appearing in the human court. It is from Velimir’s perspective.

The door opened and an old woman hobbled through. On the opposite end of the room, with the tall ceiling above her, she looked as small as a child. Her shuffling steps echoed. Her tattered dress seemed a quilt of rags, hanging limp and colorless over her hutched body. The sunlight caught on her white hair, casting harsh shade into every wrinkle on her face. Then she entered the dim light between open windows, fading into the shadow.

She stepped into the lighted middle of the room. The noise of the conversation faded as she lifted her bowed head and met Velimir’s eyes. A keenness in her gaze made him for a moment doubt her age. Though she still had half the length of the room to cross, something in her amber eyes made him feel she could see right through him. He must have misjudged her poverty as well, for now her dress seemed to fit her better—still the wear of a peasant, but a full skirt at least, without patches or holes.

A tingling raced over the back of his hand, like a spider. He scratched at it absently.

Even as she entered the shadow, he saw that her hair wasn’t quite gray anymore. It had become more of a light brown. And though he could have sworn her face wrinkled when she entered, it was remarkably smooth when she emerged into the light again. Her skin lost the deep tone of the Bhàtarians, becoming paler with every step she took.

She stopped ten feet from Velimir, at the edge of the last ring of light. Now she stood straight. Embroidery crept over her dress like ivy, changing it from a peasant’s garb into a court gown, with color creeping into the thread as vibrant as an autumn forest. A crown of flowers bloomed over her hair, now long and rich brown.

One of the fair folk.

Velimir’s attention caught on the particular way she held her hand at her side. A long, straight branch grew out of her fist. As she lifted her arm, Velimir could see that the wand attached to the veins at her wrist, the wood turning reddish as it mixed with her blood and punctured the skin. The tips of her fingers became stained a dark, earthy brown.

Writers should be aware of the tradition of myth, landscape, history and culture when they set out to write about an existing or an entirely imaginary world. We as individuals would not be who we are without the myths, landscape and history of the towns where we grew up, the family stories passed down from grandparents, or even the humorous tales that are passed around Berry. In the same way, in order to have a fully developed character, one must give thought to their surroundings, the influences on their heritage. It is by exploring this relationship that fiction can leverage myth to create a tale as diverse, wild and vivid as the stories of Wales.

(Note: All my excerpts have been shortened for this post, though they were read at full length during the presentation. This is why they are a bit more choppy.)