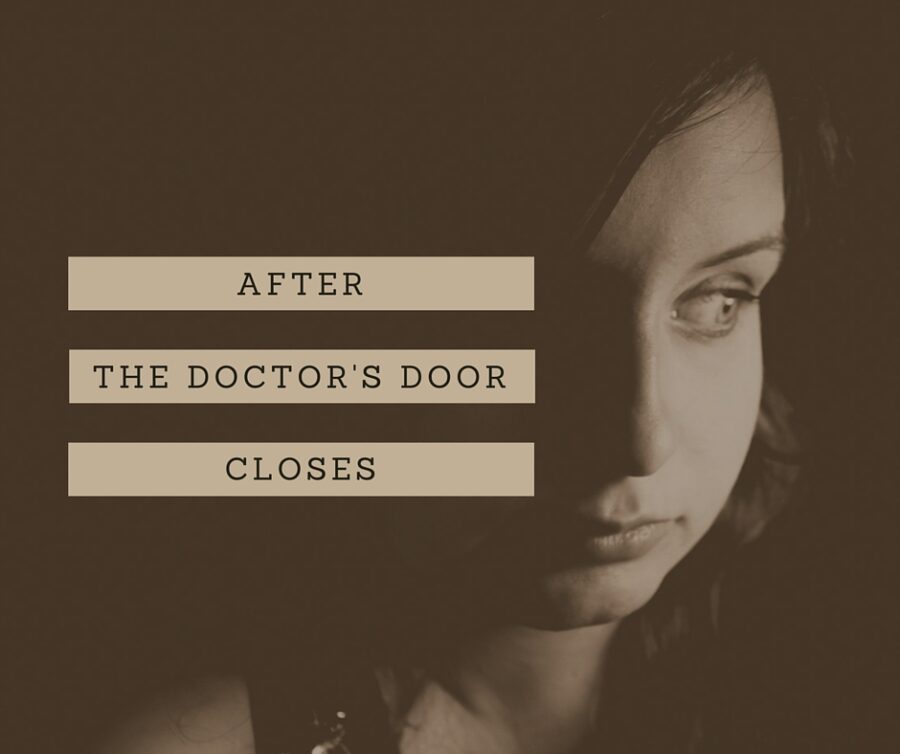

“I’ll send someone in to schedule the test,” the specialist says to me. “Wait here a moment.”

I nod and watch her leave. As the door clicks shut, a sinking, sick, hollow gap grows and groans in my chest. I shrink against the uncomfortable chair, stare at my hands or count the number of tiles on the floor. I don’t look at the posters of disease on the walls. I already read them earlier.

It never gets better, this moment after the door shuts and there is only you and the white white room. It never changes.

The me who waits for someone to schedule a test is 21-year-old me cradling a broken finger and fearing surgery. It’s 18-year-old-me clutching the side of the table with burning holes up her leg from the procedure. It’s 17-year-old-me wondering how many vials of blood it’s going to take this time.

Even when I was younger and my mom was there, it was still this. This panic that oozes more than it spirals. This settling down, down into fears that have no names. Yet.

This is an autoimmune disease. A chronic illness. Another diagnosis.

It’s a weekly, monthly, twice-yearly reality of living with these diseases. It’s the word “cancer” that hovers in the air even though the doctor doesn’t speak it.

It’s just part of my life.

In normal days – semi-normal days – my version of normal days – I don’t always feel it, the drag of seven years of medical reports anchored to my leg. I do the things regular folk do, like go to work and talk to friends and make jokes about my brother’s wedding or my sister’s Slytherin ways.

I’m fine.

Yet the anchor waits, heavy as ever, for my guard to drop. For words like “test” and “results” and “symptoms.” And I am shattered, again. Broken, again. Sometimes I think that I am only ever better so that I can be broken. Again, again, again.

I sit in the room and count tiles. Wonder why they went with a blue and cream color scheme. Wonder if I should text my mom. Decide not to. I’ll call later.

There is no cure for me. There is remission, maybe, for some of it. If the drugs and stars and prayers align. But there is no cure. The most I can hope for is to plateau. For the damage that’s done to be the only damage done. For the fingers crushed to be the only ones broken, or the pancreas dead to be the only organ failing, or the celiac and other gut problems to be the only ones developing.

Constantly, constantly I wonder (and try not to wonder) if this is the best it gets. If someday I’ll look back on my hard days and think them easy.

And what will I do if the arthritis spreads to my hip? Remember when it couldn’t bear weight that morning, and I barely managed to walk the dog?

And what will happen when it spreads through my toes? It’s already started.

And what if what if what if

Scold myself back into the room, back into the present, alone. Clench my jaw, lift my chin.

Don’t ask why. There are a thousand cliched answers and I know them all. I know they’re as hollow as this room, as hollow as my chest. I know. So don’t ask.

Don’t wonder. Don’t think. The two are the same and once I start there is only darkness. There is only the hole full of needles and inverted photos and blood vials.

Someone once said that in situations like this there’s no choice but hope. I wish I could measure out my heart now, pour it into a spoon, offer the alternative. I wish she could measure me out hers.

Because there is no end to this. There’s no hope for restoration. There is only distraction.

And after the nurse puts me down for a date, hands me directions for the test, sends me back into a world not filled with artificial light, distraction is what I seek. Distraction’s on my tongue when I call my mom and coo away her fears. Distraction when I turn to my storytelling and my deadlines. Distraction at work or in conversation.

I’ll cope later. After the test results come in. After these feelings settle into safety. After I forget, for a while, that empty room.

I’ll cope while I wait for next time.

Note: I wrote this around the time of my diagnosis with gastroparesis (now almost four months ago). But it feels appropriate to share.